Authoritarian populism in Hungary: restructuring, crisis and housing

2013.03.29. 03:28

Hungary is in the news these days. The most recent event that brought this country to the headlines was the modification of the constitution (now official called the Fundamental Law). Although it has not been the most outrageous thing that the current regime has done, the modification is the culmination of a long process of de-democratizing Hungary and quite emblematic of what has been happening there over the past few years both politically and economically.

Hungary is in the news these days. The most recent event that brought this country to the headlines was the modification of the constitution (now official called the Fundamental Law). Although it has not been the most outrageous thing that the current regime has done, the modification is the culmination of a long process of de-democratizing Hungary and quite emblematic of what has been happening there over the past few years both politically and economically.

The 4th modification of the constitution

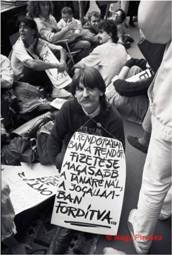

About two weeks ago, 70 people occupied the headquarters of the ruling party FIDESZ. Many of the participants were university students, but it was undoubtedly a broad coalition of participants including members of the LGBT movement, human rights activists and the homeless advocacy group The City is for All. Participants of the sit-in protested against the 4th modification of the Constitution, which would limit the autonomy of universities and the rights of university students, restrict the definition of family to marriage and parental relationships, reserve the right of the state to define legitimate religions, allow local governments to ban homeless people from certain parts of municipalities and seriously limit the jurisdiction of the Constitutional court. At a more general level, protestors stood up against the large-scale authoritarian and right-wing restructuring of Hungarian politics, society and economy that has been going on since the election of FIDESZ in 2010.

The nonviolent protestors were met with a vicious reaction: instead of calling the police to intervene (in fact, the police that came to the spot were sent away by the party), the employees of the FIDESZ headquarters physically struggles with protestors, thugs were brought in to keep protestors out of the building and counter-protestors – supporters of FIDESZ – surrounded the building and intimidated participants.

The nonviolent protestors were met with a vicious reaction: instead of calling the police to intervene (in fact, the police that came to the spot were sent away by the party), the employees of the FIDESZ headquarters physically struggles with protestors, thugs were brought in to keep protestors out of the building and counter-protestors – supporters of FIDESZ – surrounded the building and intimidated participants.

Over the past few months, grassroots mobilization has been very strong in Hungary. There have been many more traditional street protests with tens of thousands of participants, but civil disobedience and direct action have been also been used more intensively. So far, this sit-in has had the highest stakes and has probably been the most disruptive – not in a physical sense (the protestors remained nonviolent throughout), but in terms of its impact on the political process.

Establishing hegemony

After its sweeping victory in 2010, FIDESZ has had two thirds majority in the Hungarian Parliament. As a result, they basically have to face no political opposition at the national level and they also dominate local governments.

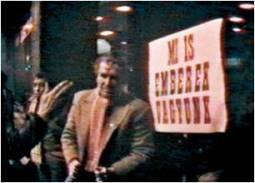

It is important to keep in mind that the founders of FIDESZ (the current speaker, the Prime Minister and the President of Hungary among them) played a very important role during the regime change. They were all part of the semi-legal democratic opposition that fermented some of the political changes in the country at the end of the 1980s. In images from the late 1980s and early 1990s, we see the Prime Minister with a poster behind him that says: “I want to live in a country where the law doesn’t only protect Coca Cola” and the current speaker of the house engaging in a sit-in holding a placard that says “In a police state, the salary of the police officer is higher than that of the teacher. In a state ruled by law, it is the opposite.”

However, today, all of these politicians and their party represent a very different ideology and have initiated a massive right-wing authoritarian reorganization of the country. First, abusing its two-thirds majority, FIDESZ changed Hungary’s constitution without any meaningful public participation. The new constitution watered down many of the social commitments of the state and defines Hungary as the country of Hungarians and Christians. It also solidified a flat income tax, which has had a very negative impact on low-income Hungarians and very beneficial for high-income residents.

However, today, all of these politicians and their party represent a very different ideology and have initiated a massive right-wing authoritarian reorganization of the country. First, abusing its two-thirds majority, FIDESZ changed Hungary’s constitution without any meaningful public participation. The new constitution watered down many of the social commitments of the state and defines Hungary as the country of Hungarians and Christians. It also solidified a flat income tax, which has had a very negative impact on low-income Hungarians and very beneficial for high-income residents.

FIDESZ also introduced many undemocratic measures over the past three years: it curtailed the freedom of the press and the freedom of religion and also challenged the independence of the Hungarian National Bank and the Constitutional Court. In addition to a legal and political overhaul, the government also introduced many anti-poor measures such as a strict program of workfare that keeps people in deep poverty, severe cutbacks on social benefits and a reformed Labor Code that significantly weakens workers’ rights, among others.

Today, Hungary is basically under a single-party rule (even though there is nominally a two-party coalition in government with the Christian Democratic Party KDNP). The government totally disregards any and all opposing opinions or positions. Ironically, only the IMF and the EU seem to able to exert some pressure. In a paradoxical way, while the EU has been pursuing an excess deficit procedure against Hungary for years that forces the government to cut social spending, it also started (and may be starting once again) a procedure against Hungary for breaching the most fundamental values of the European Union. The same with the IMF: while has provides the Hungarian government with loans that require strict fiscal discipline, it has also warned against the anti-poor and authoritarian policies of the current government.

In all, FIDESZ seems to be exercising a politics of revenge. With the 4th modification of the constitution, the party basically took all the issues that have been contentious either politically or legally since they came to power, and put them into the constitution so that they become fundamental law. In this way, not even the Constitutional Court is able to challenge them. In fact, while the Constitutional Court has not been particularly progressive (for example in 2000 it stated that the right to housing cannot be established in Hungary based on the Constitution that was in effect then), in the last couple of years, it has been the only state body the provided some checks on the hegemony of FIDESZ. Now, with its jurisdiction curtailed and almost all of its previous decisions overridden, it is a good example of the kind of revanchism described by Neil Smith at the urban scale, but now elevated to the scale of the state in Hungary.

Post-socialist hubris

Hungarian sociologist Attila Melegh uses the phrase “post-socialist hubris,” which comes from ancient Greek and refers to great arrogance and the lack of humility, to characterize the post-socialist Hungarian condition (quite eerily, it was also used to describe Hitler’s rise to power).

The current Hungarian political situation has been compared to either the regime of Hugo Chavez in Venezuela (not a very apt comparison), or to Thatcherism. If we take Stuart Hall’s characterization of the Thatcher era in Britain as authoritarian populism, it seems to be a much better comparison with the destruction of the social safety net, a war against minorities, revenge against all political adversaries in all areas of life including politics and culture and a nationalist and moralizing discourse. However, according to Attila Melegh, the situation may be neither like Venezuela, nor like Britain but more like South Korea as it was remaking itself to fit the global expansion of neoliberal capitalism: “We should not be mistaken this is not a fascist, one party system (yet), but an authoritarian structure in which its leaders dream about a new probably South Korean type growth and developments with low labor costs and much lower social security.”

Whichever comparison we find more fitting, it is important to point out that even if the Orbán regime is exceptionally authoritarian, oppressive and damaging, the crisis of Hungarian society did not begin in 2010. As the semi-periphery of the Soviet Union from the 1950s to the 1980s, then the semi-periphery of Europe and global capitalism, Hungary has been in a long political, social and economic struggle to meet domestic needs and foreign expectations. In this sense, the current crisis and its political ramifications are only a culmination of the long crisis triggered by the collapse of state socialism and Hungary’s “re-integration” into the world capitalist system that started in the 1980s.

The long crisis: housing and homelessness from state socialism to capitalism

I would like to illustrate how the long and short-term crises of Hungarian society are related through the analysis of policies around housing and homelessness, as this is the field I am not familiar with.

First, let me give you a short historical context. During state socialism, housing was a central issue. At the beginning, the stated aimed to decommodify housing and provide it for the workers as a form of entitlement, or rather reward. After the Second World War, the communist government nationalized apartments and the proportion of publicly owned housing stock reached 50% in Budapest. Most of the housing in the countryside remained in private hands. In addition to nationalization, the government developed a system of distributing housing units for families based on various criteria. The state invested a lot in new housing construction – the results are the (now) infamous housing projects, which most of their residents considered a huge improvement over their previous housing conditions.

Especially after the 1956 revolution, housing was used as one of the main tools to maintain social peace. In this sense, housing was an ideological issue that had very tangible material consequences for many-many people. Housing conditions improved immensely for all segments of the population together with other social indicators such as education, literacy, quality of life etc.

At the same time, the distribution of housing was very unequal. The socialist middle class benefited much more from centralized housing policies than the rest of the population. Those who were already in a better social position had access to much better housing and has a much higher chance of accessing publicly subsidized housing. Many workers lived in private homes, which they built and which were much more unaffordable than public housing.

In an effort to eliminate Gypsy colonies, the Roma were also offered housing in the form of what was called “houses of reduced quality.” These were almost always placed in segregated areas of cities and villages. Again, these were of much better quality than the colonies they had previous lived in but much worse than other public housing. The state’s housing policy towards the Roma – in line with many of its other policies – signaled racism as an integral element of the state socialist regime.

In an effort to eliminate Gypsy colonies, the Roma were also offered housing in the form of what was called “houses of reduced quality.” These were almost always placed in segregated areas of cities and villages. Again, these were of much better quality than the colonies they had previous lived in but much worse than other public housing. The state’s housing policy towards the Roma – in line with many of its other policies – signaled racism as an integral element of the state socialist regime.

During state socialism, homelessness and poverty officially did not exist. On the one hand, full employment was supposed to take care of all social problems automatically. On the other, those who were on the streets, did not have a job or did not fit social norms, were institutionalized in places like work therapy institutions and hospitals or jailed.

The emphasis on public housing started to change in the 1970s as the socialist economy was not able to produce enough housing units of good quality and the state started to support private construction and homeownership. This shift to market economy was visible in all aspects of economic and social policy.

While privatization started before the regime change, it took place at a great speed and without much regulation after 1990. The public housing stock dwindled – today 6% of the housing stock in Budapest and less than 3% of the housing stock in the entire country is publicly owned as opposed to the 50% and 25% during state socialism, respectively.

Privatization was more beneficial for higher classes as they could buy their apartments at a fraction of the market price. By contrast, many poor and old people bought apartments in buildings that they could not maintain on the long run (which resulted in some of them wanting to sell their apartments back to the municipality, without much success). In the end, local governments got stuck with the housing stock in the worst condition, which also had some of the poorest residents of the country. Today, local governments consider housing as a burden and not an opportunity and want to get rid of most of their housing stock.

In parallel to the increasing privatization of housing, there was an explosion of discourse around homelessness at the end of the 1980s. This was in large part due to the spontaneous demonstrations and sit-ins organized by homeless people at major train stations in Budapest in the winters of 1989 and 1990. As a result of these protests, the state was forced to provide services and these efforts lay the foundations of the social services and homeless shelter system that exists today.

In parallel to the increasing privatization of housing, there was an explosion of discourse around homelessness at the end of the 1980s. This was in large part due to the spontaneous demonstrations and sit-ins organized by homeless people at major train stations in Budapest in the winters of 1989 and 1990. As a result of these protests, the state was forced to provide services and these efforts lay the foundations of the social services and homeless shelter system that exists today.

State socialist housing policy had many flaws, but it at least existed and plans were made about how to provide housing to the general population. Since the regime change, the Hungarian state has fully embraced the most extreme version of neoliberalism regarding housing and homelessness. Today, the government’s predominant view is that taking care of housing is a completely private issue. As neither the local, nor the national state wants to have anything to do with housing, there is currently no national housing or homeless policy in Hungary. Homelessness is generally considered a personal pathology and – as Bálint Misetics has pointed out – there is a widespread idea that homeless people belong to shelters, just like criminals belong to jails or sick people to hospitals.

There are two exceptions to this general trend when the government had a more active housing policy (both under FIDESZ). Between 2000 and 2004, the government introduced subsidized mortgages. Most of these subsidies went to support homeownership for the middle and especially the upper middle class. While the state indebted itself with these subsidized loans for years to come, the housing support for low income people remained extremely small (today the generally available housing subsidy for low income people is a maximum of 30 dollars/month).

As the 2008 financial crisis was erupting into mortgage crisis, a clear division developed between the “good” and the “bad” homeless in terms of state policies. FIDESZ attempted to help out those defaulting on their mortgages by negotiating settlements with the banks and introducing a moratorium on evictions, but again this mostly benefited the higher class (many lower class people are defaulting on their mortgages and do not received any help from the state). The evictions moratorium that was introduced did not apply to those living in public housing after a while, and the moratorium definitely did not apply to squatters.

In all, despite the prevailing rhetoric about housing being a private issue, the Hungarian state seems to differentiate between housing and housing, and clearly prioritizes support for private property, home ownership and the more privileged sections of society. This approach to housing confirms David Harvey’s definition of neoliberalism a class project: if there is any state housing policy in Hungary, it aims to support the middle and higher classes who want to purchase private homes and are able to take out credit, but in no way housing for poor and homeless people.

Hungarian society is in a very bad shape today. Around 30% of the population is struggling to survive on a day-to-day basis. 30 to 50 thousand people are homeless and live in shelters, on the streets or places not means for human habitation such as forests, caves etc. The number of those on the verge of homelessness and living in inadequate housing is, of course, much higher.

Laws that criminalized homelessness and poverty were repealed after the regime change. While the harassment of people who did not have a home continued, this approach was not formalized again for a long time. In the early-mid-2000s, however, when the Hungarian economy was starting to do a bit better, there was a clear shift towards more formal measures of criminalization. For example: In 2002 the mayor of Budapest started a program to clean underground passages of “graffiti, illegal vendors and homeless people” – as his program put it. In an even more direct move in 2009, a local mayor in Budapest created homeless-free zones in his district by designating certain places where homeless people would be “banned, tolerated or allowed.”

The scale and intensity of the criminalization of both poverty in general and homelessness in particular picked up around 2010. Leading politicians started talking about the need to stop “homeless crime” and an intensive anti-homeless campaign started in the 8th district of Budapest – hundreds of people were detained for minor violations such as public urination, rummaging through garbage or sleeping on the street over a month in an effort to push them out of the district.

The peak of this new wave of criminalization was the passing of a law in 2011 that made living in public space a crime, with a punishment of up to $700. While these kinds of laws are widespread in the US, this was the only law of its kind in Europe that I am aware of. Between April and November of 2012, altogether 2200 people were charged with “habitual residence in public spaces.” In more than 1500 cases, a total of more than $180 thousand were incurred in fines for being homeless.

In a major victory in November 2012, the Hungarian Constitutional Court found this law unconstitutional and repealed it right away. And this is where we get back to the sit-in at the beginning of my presentation: this was one of the decisions of the Court that the government decided to override and write the criminalization of street homelessness into the constitution – this is the main reason why homeless activists were at the FIDESZ headquarters in March, 2013 and demanded that the modification be repealed (in addition to protesting all anti-democratic measures).

Criminalization as a response to the crisis of hegemony

As we know from Marx in his description of the “bloody laws” in England, the large-scale criminalization of poverty often occurs in reaction to a large-scale, structural transformation of the economy. While homelessness was decriminalized after the regime change in Hungary, both the social crisis and criminalization are reaching their peak.

The Hungarian state is in a crisis of both legitimacy and social reproduction. Despite the current populist rhetoric against the West, as a country on the semi-periphery, Hungary is totally dependent on the global economy and is unable to reduce the size of its surplus populations.

While the Hungarian ruling elite itself may not be in an economic crisis, they are in a political one: they need to secure their dominance in an increasingly failing society. Social services are stigmatizing and inefficient. Austerity measures are punishing the most vulnerable groups in society such as the Roma, the poor, the disabled and undocumented migrants.

In this way, it is not necessarily the economic crisis itself that triggered criminalization, but what Stuart Hall called the “crisis of hegemony” – the political failure of the ruling class to stabilize the economy and fulfill the promises of the regime change. At the same time, through demonization and criminalization, the state uses the bodies of poor and marginalized people as scapegoats in order to obscure its own failure.

I started out with a recent event, so let me finish with one. A telling example of the kind of state that FIDESZ is building is illustrated by the way in which the state handled the huge snowstorm that swept through Europe last week. While the storm had been predicted, when it occurred, the state apparatus was frozen – thousands of people were stuck in their cars for up to 48 hours on the highway with basically no help from public authorities. As a blogger recently pointed out, this situation was a good illustration of how while the state is channeling funds to local and local capitalists and establishes strict political control over all walks of life, it is unable to carry out the function of providing basic public services. The Hungarian state is definitely not getting smaller, only its role is changing dramatically.

- Éva Tessza Udvarhelyi

Presented at the roundtable on "Urbanization of Shock Therapy: Southeast Europe and the European Crisis" at the New School, New York City on March 22, 2013.