In this presentation, I will first introduce the organization called The City is for All and then move on to some of the dilemmas we have encountered in our work. I will provide more questions than answers as my questions are meant as a friendly provocation for further critical reflection.

In this presentation, I will first introduce the organization called The City is for All and then move on to some of the dilemmas we have encountered in our work. I will provide more questions than answers as my questions are meant as a friendly provocation for further critical reflection.

1. The City is for All

A Város Mindenkié (The City is for All) was founded in 2009 in Budapest, Hungary, based on the model of the New York-based organization called Picture the Homeless (PTH). While I have been involved in housing organizing since 2005, up until 2009, this was conventional middle-class activism where we worked for homeless people but not in any way with them. When I came to study in New York, I met PTH and it turned my world around. I learnt from them that homeless people need to be at the center of progressive work as active subjects and not only as objects of our compassion.

PTH came to Budapest to train us and the participants of this training became the founding membership of The City is for All – half of them were homeless and half of them allies. Today, our group has 50-60 core activists, most of whom are homeless or have experienced some form of housing deprivation. In addition, we have base of several thousand people as our supporters.

The City is for All is a totally informal and voluntary organization and we work to maintain a deeply democratic structure in terms of decision making and the distribution of tasks and responsibilities. Without a modicum of modesty, I can say that The City is for All probably represents the most well-organized and purposeful grassroots group in Hungary on the left today.

The main aims of our group are the following:

- a social and economic system based on equality and justice

We are fighting for a radical restructuring of Hungarian social, economic and political life based on solidarity. More specifically, we fight for the true political representation of homeless and poor people, against discrimination and criminalization and we want to see a very broad system of social services for all citizens.

- acknowledgment and implementation of the right to housing as state policy

We are starting from scratch in advocating for a comprehensive local and national housing policy. In our view, this includes a ban on forced evictions and evictions without alternative placement. It also means that there is housing for everyone beyond emergency shelter.

The historical background to these demands is important. During state socialism, housing was considered a public asset. It was mass produced and distributed by the state. While the system was far from perfect, social housing existed as both a concept and practice. Since the regime change in 1990, almost all housing has been privatized. Overall, the privatization process in Hungary has been an extremely perfect example of what David Harvey calls “accumulation by dispossession.” In this case, those who have been dispossessed are the Hungarian state and those living in housing poverty. Today, housing is considered a totally private issue by most decision-makers and politicians.

- political empowerment of poor and marginalized citizens

We mobilize homeless and poor people for political participation. We encourage and support them to participate through formal and informal means such as advocacy at shelters, to push for legislative change and to take part in local and national selections. Our aim is to build a mass base of homeless people and those struggling with housing issues so that we are taken seriously in policy-making.

Our methods range from running a legal clinic through litigation, petitions, community events, public forums, protests and rallies and civil disobedience, if necessary. We also use the media very intensively in our work. One of our basic principles is to form active solidarity with other oppressed groups. We try to take our name seriously: The City is really for All. For example, one of the greatest breakthroughs of the group was when we first decided to join the Gay Pride Parade. It was a long and hard debate, but by now it has become an integral part of the group’s identity. In this vein, we have also protested in solidarity with refugees, women, victims of domestic violence and the Roma among others.

In the next section, I will talk about some of the dilemmas that have emerged as we organize towards a more just society in Hungary

2. Possibilities and challenges of cross-class organizing

While our model is Picture The Homeless, we are different from them in one major aspect, which is that we welcome both homeless people and non-homeless people in our organization. This is partly a result of the fact that allies were key to founding the group, but also based on convictions and strategic considerations. So, why are we choosing this hybrid model?

First, we believe that homelessness is not only a material issue, but a political one and housing poverty will not be solved without the political emancipation of poor people. We place a huge emphasis on recruiting homeless activists and train homeless leaders. We embrace the slogan of so many other movements of marginalized people: “Don’t talk about us, talk with us!”

At the same time, we also believe that homelessness is not homeless people’s issue but everybody’s problem. We think that class segregation is not useful for our overall goals. Cross-class cooperation is at the heart of our work and we consider it a daily exercise in active solidarity and the emancipation of all involved.

Of course, we start out with very unequal relationships in the group. Allies tend to be more highly educated, have much better social connections, have stable family backgrounds, a job or some steady source of income and higher levels of self-confidence than homeless members. Homeless activists live in very precarious situations – their activism is sometimes an act of miracle in my eyes.

In order to minimize these inequalities and undermine the class hierarchy that we bring into the group, we have created an organizing process and structure that 1) uses the advantages of allies to the benefit of the whole group, 2) minimizes their possibilities of control and 3) also empowers homeless members.

In a way, we see our work as an experiment by modeling the kind public sphere that we want to see taking shape. Some of the dynamics we use to deconstruct class hierarchy within the group are the following:

1. We hold many trainings where homeless people and allies take turns educating each other, For example, the volunteer lawyers in our Streetlawyer program have to take part in a training that held by homeless activists. On the other hand, we organize trainings where allies teach homeless people about something they are familiar with (e.g. using Internet or housing policy).

2. Only homeless members can represent the group in public, including the media. If a non-homeless activist appears in public, they can only do so together with a homeless member. People who represent us in public take turns and must be nominated by the group based on a flexible set of criteria. We always thoroughly prepare everyone who appears in the media as it can often be a damaging experience and may backfire for those who are not used to that kind of attention.

3. The group has no appointed leaders and all decisions are made collectively. Decisions that affect the whole group can only be made at the weekly meetings where everyone is able to participate and decisions can be reached only through a consensus. No voting, no decisions on the mailing list or in small groups!

4. At our meetings, facilitation techniques are used to minimize the influence of more powerful members such as allies over homeless activists, men over women and old over new members.

These processes have at least two consequences for our work: 1. they slow it down considerably and 2. they make it more thorough and consistent. In fact, this approach has been called “slow politics” in the case of the South African Abahlali movement and we follow the same principles. The point of all these rules is to ensure substantive rather than numeric representation, encourage meaningful participation and avoid the creation of an elite within the group.

Of course, the balance in not (yet) perfect and we have to work a lot more. Even if numerically fewer, allies have many more things at their disposals such as skills and material and social resources. One of our big challenges is that homeless people tend to respect allies more than each other. Disruptions in the personal lives of homeless activists can disrupt their activism and render it totally meaningless for the moment. While allies go and give presentations at conferences (such as this one) and expand their academic resume, many long-time homeless members still don’t have a regular job or a home. Also, homeless activists have a hard time using their activist skills outside of the group and they tend to be marginalized in movements that do not know how to interact with people of a different class. So, things are definitely far from perfect!

However, I often explain our work as a labor of imagination: we expand the realm of the possible by imagining that things can work differently and then we gradually move into and fill up the space we have thus created. Cross-class solidarity and active cooperation is definitely in this realm. We have started it, but these challenges and contradictions are constantly with us and we need to reflect on and analyze them even more, and also learn from the experiences of other movements.

2. Questions of geography

The City is for All is the Hungarian translation of the “right to the city” and is part of the emerging academic and activist focus on cities as major sites of struggle. But after all, in Eastern Europe, the right to the city is an imported concept and it cannot be adopted uncritically. Is the city the right place for transformational activism in today’s Eastern Europe? If yes, how do we define the right to the city for ourselves?

As elsewhere, the city is a major site of capital accumulation, investment and consumption as well as dispossession in Hungary. The per capita GDP in Budapest is three times that outside the city and 40% of companies are in Budapest. At the same time, there is 8 years of difference in life expectancy in the richest and poorest districts and the average income of the poorest district if half of the richest ones. These all justify our attention to the city, but there are also some questions that I would like to raise.

1. poverty and dispossession outside the city

Despite the huge inequalities in Budapest, poverty in Hungary is concentrated outside of cities – poverty is more and more ruralized as many poor Roma and non-Roma Hungarians live in ghettoized villages. Do we ignore suffering outside the city by focusing on the urban? Or to put it more constructively, how do we integrate nonurban geography into our struggles?

2. different kinds of urbanization

In Eastern Europe, 70% of the population lives in cities. But this is very misleading. In Hungary, for example, Budapest has 2 million residents and the next big city has 200 thousand, one tenth of the capital. City status brings prestige and money, so very rural places meet the formal requirements without being cities in a political or social sense. How do we define city for our purposes and how do we integrate different kinds of urbanizations into the practice and discourse of the right to the city?

3. danger of intellectual bias

Academics and activists shaping movement discourses around the right to the city tend to be – nor surprisingly – urban and cosmopolitan. I myself was born in Budapest and feel very connected to the city. Are we addressing issues that are important for us because this is where we live or are we addressing them because they are truly the “most important”? This is of course provocation, but I think that class bias is definitely worth further exploration in terms of movement building in Eastern Europe.

4. politics of scale

While our everyday personal experiences connect us to the city, economically speaking, Eastern Europe as a region probably makes more sense than its individual cities. It could also be argued that the European Union has more impact on Hungarian politics than our own government. However, EU-level action is very rare and if it happens it is very difficult to do it from the grassroots: European politics is very bureaucratic and there is no established “European identity” in Eastern Europe. Finally, Hungary is the country that is the most dependent on foreign capital in the entire region. In a way, Budapest is so deeply embedded in the flows of global capital that it may not be much more than a nice scenery for processes that go way beyond our local, national, regional or even European realities.

These different scales of politics are, of course, deeply embedded and intertwined with each other. Do we need to act on all these scales? And if yes – which I assume is the answer – how do we do that without losing integrity and social base?

Overall, I think that if we want to imagine urban uprisings at the global scale, as the title of the panel indicates, we need to work out the issues that I have spelled out even more. I hope my presentation is a useful contribution to that discussion.

- Éva Tessza Udvarhelyi

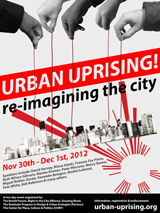

Presented at the Urban Uprising conference at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York on November 30, 2012.